The Haiti-Lansingburgh Connection 1805

Yes, you read that correctly. What connection could there possibly be between the village of Lansingburgh and the Caribbean island of Haiti- then called Saint-Domingue?

An intrepid and possible fool-hardy entrepreneur named Simeon Johnson left his wife and several small children in Lansingburgh and went to literally make his fortune trading in coffee in Haiti at the end of 1805. How do we know this? Simeon wrote letters home to his wife from 1805 to 1807. A descendant, Alan R. Leake, gave them to the Hart Cluett Museum. They gave an insight into Haiti and indeed the life at the time, besides relating Johnson’s adventures.

Simeon Johnson was born in Connecticut to Samuel (1737-1804) and Ann Hopkins (1742-1816) Johnson. He married Lucretia Ranney in Connecticut about 1790, when their daughter Julia was born. Lucretia was the daughter of Hezekiah (1742-1826) and Lucretia Hartshorn (1746-1784) Ranney, of Rhode Island. Hezekiah was a school master. He moved to Saratoga County in 1795. Lucretia and Simeon also had sons William and Frederick. Lucretia’s sister, Charlotte (1776-1864) was married to Eli Judson (1771-1821). They also lived in Lansingburgh.

Dec. 2, 1800 Lansingburgh Gazette

I think that the Johnson family moved to Lansingburgh around the same time as Hezekiah moved to Saratoga County. A Simeon Johnson appears in the records of the NYS Supreme Court, suing six local men from 1793 to 1797, and being sued by two himself. Simeon appears on the NYS Assessment roll for 1801 in Lansingburgh, with real estate worth $2,360 and a personal estate of $500, a substantial amount.

Simeon was involved in several enterprises. In 1800 he opened a general store and an inn or public house called Johnson’s Hotel. The front steps of the inn were used as the location for several mortgage sales in the next couple of years. He also plunged into community affairs. He was listed on a committee to promote Stephen Van Rensselaer as a candidate for NYS Governor in 1801 (1 Apr 1801 Lansingburgh Budget), and was elected one of three coroners for Rensselaer County in 1800 (5 Aug 1800 Lansingburgh Gazette). He was one of the original subscribers to the Lansingburgh Free Academy in 1803. Simeon seemed headed for success in his new community, expect he seemed quite litigious.

Sadly, for us today, Simeon’s letters only hint at the reasons he left his home and family and travelled to what must have been one of the most dangerous places on earth, Saint-Domingue in 1805. For a brief period- from 1795-1809, the island was under French control, but it was spilt between the French and Spanish most of the time. Of course, today the island is split between the Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic and French-speaking Haiti. The Haitian half is still one of the most dangerous places on Earth.

Jean Jacques Dessalines (1758-1806) Emperor of Haiti

By the end of the Seven Years War in 1763, the French colony of Saint-Domingue exported indigo, cotton, and sugar to the world. One-third of the Atlantic slave trade passed through the island as well. in 1791, a slave revolt led to the Haitian Revolution. Toussaint Louverture declared the Saint-Domingue’s independence in 1802, but Napoleon sent a French invasion force that same year. General Jacques Dessalines declared independence again in 1804 and may have slaughtered the remaining French population, about 5,000 people, as partial pay-back for the thousands and thousands of Blacks who had been slaughtered by the French. Dessalines declared himself Emperor of what was now called Haiti in 1804. This is a very brief summary of the tragic, complicated, and tumultuous situation into which Simeon inserted himself in 1805.

Simeon lived in Gonaives, a seaport in the northwest part of Haiti. Though there are hints that he had been in Haiti from at least August 1805, the earliest letter that survives is from December 26, 1805. He reports that he is in perfect health. “Indeed, I feel ten years younger than when I left home.” This is remarkable given that the Caribbean islands long had had the reputation of being graveyards for people going there to live. Simeon was worried about his wife’s health, which had been poor when he left. He had not heard from her at least since August. In a later letter we learn that Simeon was particularly worried as Lucretia was pregnant when he left.

The next two paragraphs of the December letter give hints of why he may have left: “I dare yet to… anticipate the time when I shall again meet my family, when every painful sensation shall be buried in oblivion… It is a consolation… that my absence may hereafter be beneficial to my dear children.” “However grossly the Jaundiced eye of Jealousy may have discolored, however wickedly the tongue of Slander may have exaggerated… I should… feel pleased were an invisible being offered to house round my head, note my actions & immediately convey them to her bosom… no one action would make her ashamed of her husband…” In a letter from January 1806, he adds that he is so engaged in business every day that “my mind {is} no longer tortured by ten thousand unpleasant and perplexing circumstances.” “I flatter myself that I am now so firmly established… that whatever malice may let fly from across the Tropic will be entirely harmless to me here.”

In the letter of January 23, 1807, he adds that he found “my steady faithful attention to business… has gained me the esteem & confidence of all Americans in the Island… it in a great measure consoles me for all the privation & dangers I have to encounter. My success will sanction the measures I have taken in leaving my family & friend in America in the manner which my peculiar and desperate circumstances made necessary.” What is he trying to tell us???

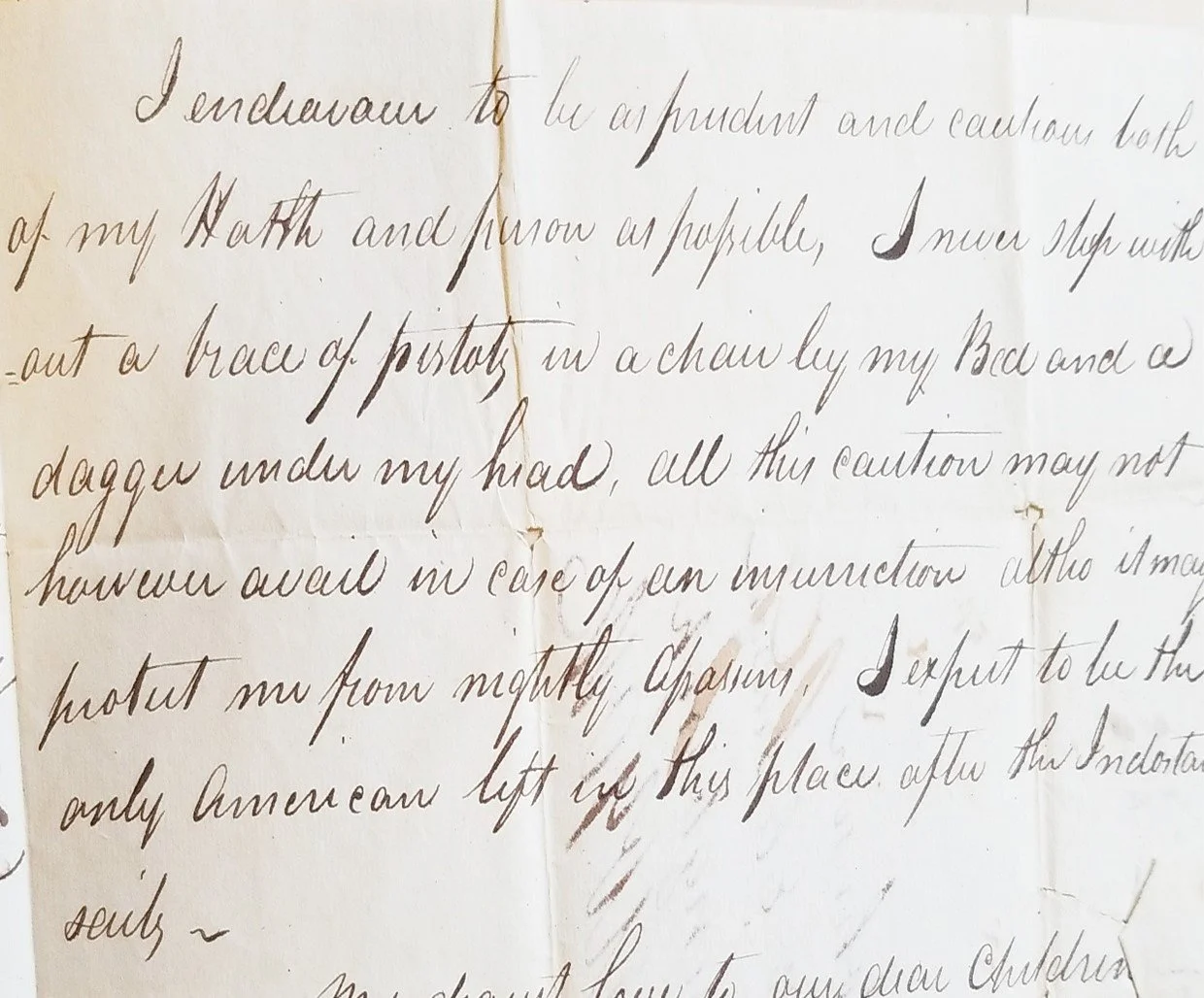

April 26, 1806, Simeon Johnson to his wife Lucretia

As of January 1806, there were several American vessels in the harbor at the Gonaives. Simeon hoped that one from Baltimore would be able to take a letter there, then on to Judge Masters, then on to his family. Josiah Masters of Schaghticoke was a member of the U.S. Congress at the time and a judge of Rensselaer County. Simeon may have known him as he was also a subscriber to the Lansingburgh Free Academy. Part of each letter home described how he plans to send it and future letters, and how Lucretia could send letters to him. It was a complicated process, with no postal service existing between the US and the island. Letters were passed through various sea captains and ports, then via people that Simeon knew in the U.S., like Masters.

We learn that Simeon was working as an agent for Powell, Kane & Company, traders. He says the owners planned to depart Gonaives in the summer, leaving him in charge. He would have had to purchase a cargo and arrange how it would be sent to the U.S. In the first of what would become a pattern, Simeon describes a trading venture of his own, which he expects will bring him a large profit, all things going well. But everything is at the which of the volatile Emperor Dessalines, and he fails to make the money. “I did not expect to make my fortune here in a day and shall endeavor not to be too much elevated by good or depressed by bad fortune but with patience & perseverance take things as they come.” He reports “Money is extremely plenty here. It is carted about in drays (wagons) with as little ceremony as bags of wheat with us. I presume that within two weeks I have passed through my hand at least one hundred thousand dollars.”

Simeon spent all his time either working or with music. He worked from sunrise to 2 or 3 p.m., then read or played the violin. The society of the “Indigenes”, presumably the Blacks, “is not desirable or pleasant and for American Society, it is often over the Bottle or at cards- either of which would destroy my confidence with my employer.” Finally at the end of January 1806 Simeon had news from Lucretia, via Judge Masters, reporting the safe birth of a child, sex unknown.

But now the reality appears: “How long things will remain peaceable here is extremely uncertain.” The Napoleonic wars were taking place in Europe, but if peace came there, Haiti could be invaded again by the French. Even the local Haitian soldiers were unpredictable. They attacked several American trading ships as they left the harbor at Gonaives from the nearby forts. And in February 1806 the U.S. Congress adopted an embargo on trade with Haiti. On the one hand, the Haitian revolution embodied the principles of the American one, but on the other, politicians in the U.S. feared that the insurrection of slaves in Haiti could inspire something similar in American slaves. His boss’ last ship, the “Indostan”, was to leave at the end of June 1806. Simeon planned to ship about 2000 pound of coffee he had purchased on board her, “to be disposed of for the benefit of my Family and Friends.” When that ship left, he would be the only American left in Gonaives. He slept with “a brace of pistols in a chair by my bed and a dagger under my head.” He admitted “all this caution may not avail me in case of insurrection.” (April 26, 1806)

Henri Christophe c. 1816 by Richard Evans. General and then self-proclaimed King of Haiti

To Simeon’s surprise, ships continued to arrive in Gonaives after the embargo- he does not specify their nationality- so he continued to be able to act as a trading agent and make some income. His house became a center of hospitality with no other Americans available. Then on October 29, 1806 he reports the assassination of the Emperor Dessalines, “of all despots that have ever existed perhaps he was the most bloody & cruel”. He said that General Henri Christophe had taken his place and “our fears are now at an end… my hopes are now more sanguine and my prosperity more brilliant.”

In reality, the island of Haiti now had two government and a civil war, with Christophe ruling the northern part of the island and Alexandre Petion the southern. By the next surviving letter, in January of 1807, this truth was clear to Simeon. He told Lucretia, “the account you may receive of the new troubles in this island may alarm you… Americans however who mind their business have nothing to fear.” Indeed, there were news articles in the “Lansingburgh Gazette” and the “Northern Budget” in Lansingburgh about the troubles in Haiti.

Despite his protestations to Lucretia that all was calm in Gonaives, by February 1807, Simeon decided to leave Haiti for London. He had purchased a large amount of coffee, which he planned to sell in Europe for between $16 and $18,000. He arrived in London by May 1807 and sent four or five letters to Lucretia by different ships, hoping that one would reach her. His new plan was to plan a trading voyage back to Haiti, hopefully as part-owner of a ship. I have to add that every letter reported a new scheme to make money.

In the end, Simeon did act as an agent for a large trading house in London, selecting and purchasing for them a cargo worth about $50,000 to ship to Haiti. In a long letter written between July 10 and 16, 1807, he reported he would sail on the ship as supercargo, that is the representative of the trading house, responsible for overseeing the sale of the cargo. This would earn him a substantial commission. And he had a part owner’s share in the cargo as well, so hoped to make an amazing $12,000.

Miniature of Simeon Johnson painted in London, 1807. Owned by the Leake family

Before leaving town, Simeon took some precautions for his family. He sat for a miniature portrait, which survives in the family. This was in case he perished in his travels, so his children could see their father. He sent some business contracts along with the letters, helpful to Lucretia in case anything should happen to him. He told Lucretia not to share her letters with anyone and that he was sailing as an Englishman, on an English ship. It was illegal for Americans to trade with Haiti. If the ship were captured (privateer raids were common), he would have to destroy his identity papers.

The final letter from Simeon is dated September 20, 1807, from Baracoa on the island of Cuba. Within sight of Haiti, his ship was captured by a French privateer and taken to Cuba. He described a desperate and bloody battle with the privateer, in which he “was stationed as Captain of Marines on the quarterdeck”, but reassured Lucretia that he was fine and being treated well. He was fluent in French, which was coming in handy, and even had hopes of buying the captured ship at a steep discount! Simeon died November 5, 1807, under what circumstances is not known. There is a tombstone for Simeon in the Wilcox Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut, which says he died back in Gonaives, Haiti.

We can only imagine what was going on with Lucretia and her children while Simeon was away. There is no indication that he ever had a letter from her. She must have communicated with others- there is the report from Judge Masters about the new baby- but he never mentions what was going on at home. Meanwhile, the “Lansingburgh Gazette” reported on November 11, 1806, that two parcels in Lansingburgh belonging to Simeon and Lucretia were being sold for non-payment of the mortgage. The ad indicates that Lucretia had already left town. the 1810 US Census lists Lucretia living in Albany in a family with one female 26-44 - presumably herself- one 16-25- Julia, six males from 16-25- who were they?, one male 10-15, and one under 10. Was she operating a rooming house? She continued to live in Albany, moving in with daughter Julia and her family, then with a grandson, the poignantly named Simeon Leake, and his family. Lucretia died in 1859 and is buried in Albany Rural Cemetery.